The Quiet Work: An Engineer’s Reflection on Influence, Credit and Culture (2)

Part Two: Buying into our insecurities

I explored various ways to influence an audience on social media, grow a following, and embrace the new era of marketing. I’m still unsure if I want to dive into it. In conclusion, I might be a bit cynical. However, the quiet creation is where I’ve expanded my knowledge and advanced my career. So, we’ll see. Maybe one day I’ll show up on a reel (unlikely, but you never know!). I still rely on credits. I still believe in crediting engineers as the best form of marketing.

However, the way we credit engineers has changed. We used to rely on the inner sleeves of CDs and vinyl (this was before my time, let’s be real…). Now, we depend on the artist to remember to include us in social media posts or distribution platforms. Even then, Spotify does not recognise mastering engineers. Online distribution often offers little more than just ‘engineer.’ So, we’re frequently left out. The small number of crediting platforms have bridged the gap during the transition from CDs, the Napster meltdown, and the rise of streaming.

The few times I’ve claimed profiles on valid crediting websites; there have been around 30-odd tracks to my name — despite having over 300 credits on my portfolio. It seems like the importance of crediting dropped for a while as independent musicians dealt with their distribution. Maybe there was a lack of education about crediting. Labels ensured this was always done, but the market has changed, and DIY processes are the common way of making music.

Despite this gap, it seemed pretty good for a while. We were filling out our credits on crediting websites, claiming profiles and songs, thinking this would be the new age of crediting. I ensured there was a bold “Mastered by Tahlia-Rose Coleman” at the end of all my file deliveries to remind artists: “Hey, this is what we need to survive. It takes you less than two minutes to copy and paste it into DistroKid etc. Thanks!” The crediting issue seemed to be back on track. My main industry issue (which, to be honest, hasn’t left) was with the mix engineer category at the Arias. Where’s mastering? Why do you only consider albums mixed — what about singles? (should this be critiqued in a blog perhaps).

Anyway.

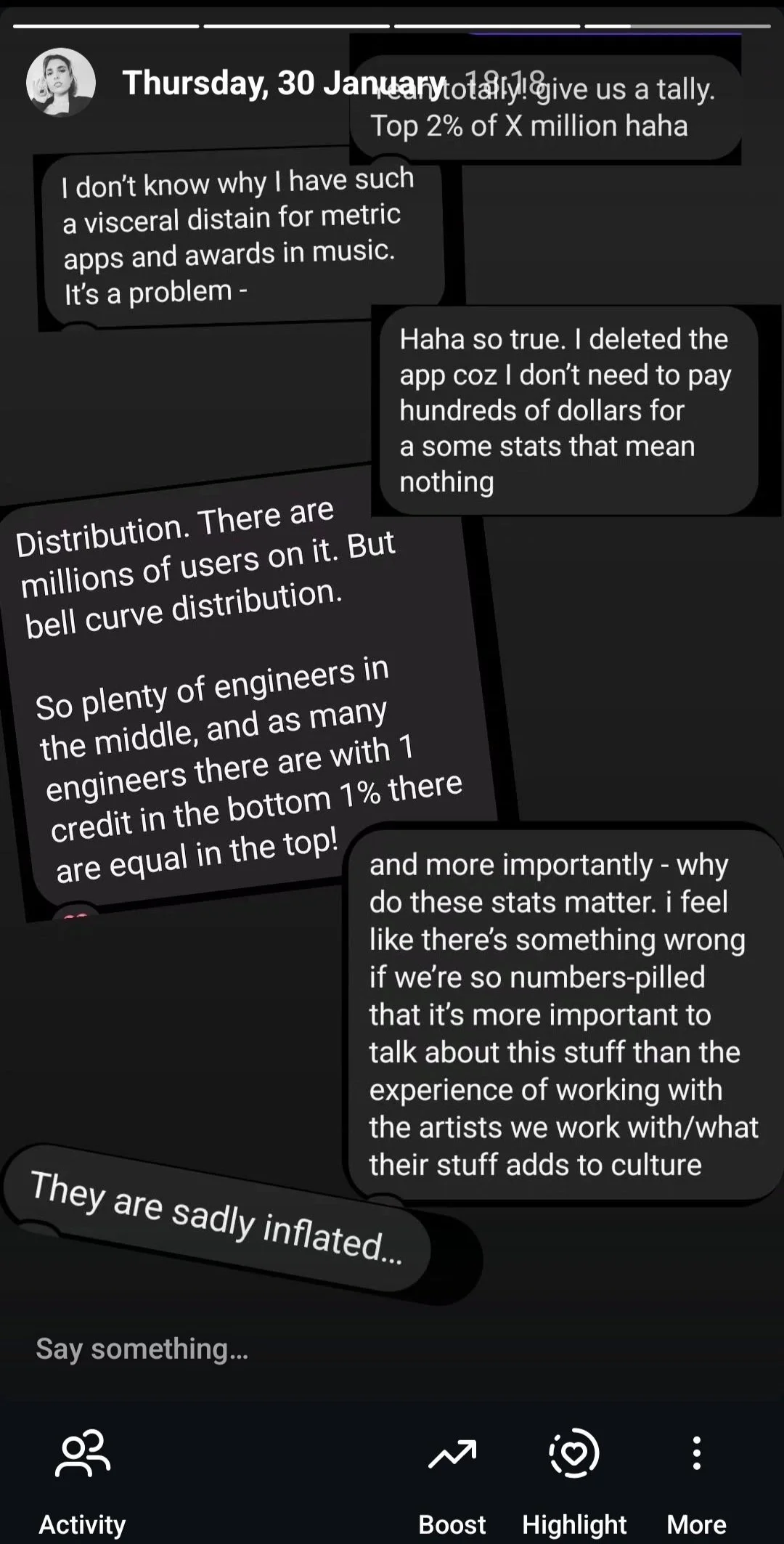

This was the current concern until I saw people posting tiles on social media: “X is in the top 1% of mixing engineers.” … “X is in the Top 1% of songwriters.” Eventually, I asked my very small following, “What’s up with this?” The consensus: it’s not real, the numbers are inflated, and it makes us feel bad. The one upside? It supported an engineer in getting their visa to move overseas.

Commentary on Muso.Ai from the community

Muso.Ai

The newer crediting website/app is called Muso.Ai. It’s a music crediting business that also provides streaming analytics of songs you’ve worked on. From there, you can purchase plaques and create social media tiles to share milestones and achievements. At face value, it sounds like a great way to follow your progress, share and promote your engineering work, and push your microcosm of collaboration. On another level, a business has grown that directly profits off our desires to be the best and compete against one another.

On the free tier, it has a crediting page with your work and highlights all the other engineers, artists, and songwriters you’ve collaborated with. The collaborator’s section highlights other people you work with on your profile. It’s an easy way to support and promote each other without lifting a finger. Thanks for that, Muso.Ai. It gave me a good throwback to projects I’ve done over the years and I had a listen to old pieces I had a part in. I saw artists and producers show up connected to me that I hadn’t spoken with or seen in years. It was like a beautiful spiderweb of all the people who’ve contributed to creativity. It was also like a bit of a graveyard of people who came and went. The cool thing was that you could click on their profiles and, if claimed, it would show you all they’d worked on and who they worked with. Overall, I found this to be a great space. The way the platform moves and works is akin to Spotify. It’s the engineer’s space. Our space to be recognised and show our portfolios.

I was also impressed with their due diligence in ensuring that all credits were correct. A staff member emailed me asking for further evidence and information that I had mastered a couple of tracks I had uploaded. I mean, I wasn’t going to lie and say I mastered a Dua Lipa song, but you never know… so I emailed back some screenshots of the booking forms from my website, and we were good as gold. I appreciate a business that’s pushing for accurate crediting. It’s an issue we as engineers have struggled with for a while now. That’s all fine.

Then there’s the paid tier.

The paid tier gives you the ‘Milestones & Charts’. It shows you how many streams you’ve accumulated across all tracks on all platforms. I initially got the 14-day free trial to see these statistics, as I was filling out an application and didn’t quite know how many streams I had accumulated, and I needed the figures.

To be honest, it was cool. I assumed the work I had done maybe amassed a few hundred thousand streams — it was in the millions. I suppose in today’s realm that’s nothing. We care about the billions now, not the millions of streams. Anyway, I was chuffed. Imagining that many humans in one space listening to your work puts it in perspective. Millions? Now that’s stage fright. That’s a great result from working with Australian artists.

As we know, the Australian music industry is small and slow on the uptake. As I write this, Riptide by Vance Joy is STILL number one on the Aria Australian Singles Chart. There are zero Australian artists on the Aria top 50 singles chart. It’s tough out there. Trying to have a full-time career as an audio engineer in Australia is tough. It’s all relative.

There is already a bit of comparison and competitiveness, and the bar only gets higher. We aim for streams in the millions, the hundreds of millions, and then the billions. That’s incredibly difficult without luck, a song randomly blowing up on TikTok (I wish this wasn’t a determiner of music but here we are), or a label with a lot of money pushing and marketing you. On social media, amongst the engineers, only those with insane stats post their titles: “X has 1,000,000,000 streams.” And so they should. What a statistic… Can you imagine one billion people all standing together? That’s a big number.

I don’t have as big of an issue with streaming analytics. They’re on all music streaming websites and we’ve dealt with them for a long time. It is cool to see how far your work has reached and to have that in a website that can accumulate streams from all platforms into one space helps a lot. Yet, these streaming numbers are arguably more important to the artist or producer who earns money from the streams. For engineers in Australia, it’s arbitrary. If you mixed, mastered, or engineered the track, you are paid a lump sum. We don’t get paid royalties. If a track gets 100 streams, or one billion streams, I still get my $140. Sharing streaming analytics can be a fun way to show the reach of our work. That’s fine enough. But if you tie your worth to streaming numbers, that’s where issues can arise. As with any space that uses statistics, comparison detracts from the work you do. Numbers aren’t the true value of your creative output. Don’t tie it to your statistics.

The second part of the paid tier includes the ‘charts’. It looks like a music chart, like the Billboard Charts or the Aria Charts. They’ll number you, assign you a ‘score’, and then give you a percentage of where you sit globally amongst your peers. It’s not easy to find information on their website that explains their scoring. I assume it’s a mix of the number of credits and streaming numbers you have. Interestingly, you only need one credit to be in the top 50% of engineers in any particular category.

I somehow hit the top 5% in mastering engineers, and I thought “That’s got to be a joke.” As a young engineer, with a small portfolio, with no label projects, that’s surely incorrect. The thing is, there’s no end goal with these statistics. Those who are in the top 1% of engineers are among thousands. The number only gets smaller — the top 0.001%, 0.0001%, and so on. I wonder if the satisfaction of finally reaching the top 1% is short-lived once you realise that relative to the Grammy winners, it’s still far from an end goal.

The ‘milestone’ I hit after uploading my credits to the website

In some ways, it can be a great tool that encourages us to keep at it, to get better, and to breakthrough in the industry. It was designed by engineers after all. In other ways, we now have a direct comparison to our peers.

Did you immediately start searching up all the engineers you know to see what their stats are? I did. Most of my peers in the mastering field are 10+ years my senior and have a lot more experience. The comparison doesn’t make sense — neither do the charts. My old mentor is in the top 1% of mastering engineers with billions of streams. I am in the top 5% with a few million streams. The math doesn’t math that well.

I won’t pay attention to it much. I know that given my age, experience and location in the world, I’m not going to be one of the top engineers right now. I’ve been busy studying, I’m distracted, I don’t market myself well and I don’t have any awards. I note though… this mental detachment from my ‘statistics’ didn’t come without years of severe imposter syndrome.

Perhaps I should own the title and start marketing myself as an engineer in the top 5% globally. Maybe I should lean into it as others do and have that unbridled confidence to make noise and show off. But I haven’t so far. I’ve just found the statistics game amusing.

To get the chart analytics, you must pay money. It’s $120USD annually ($186AUD). The owners of this business have monetised our insecurities and they are making bank. In Australia, where the industry is struggling, it is arguably an unnecessary expense to compare yourself to your peers. I’ll repeat that.

Muso.Ai profits off your desire to compare yourself to others.

The creators of this website knew what they were doing. We humans are obsessed with statistics, productivity and growth. I would know, as I have a smartwatch that analyses my health 24/7, and I pour over the numbers wondering how I can improve my personal ‘stats’. My Instagram is a business profile, it has analytics. So does my website. I often look at these and plan ways to improve my ‘reach’, convert clicks to sales, and retain followers. It’s not new, and we all love it because it gives us a tangible way to watch our growth. Healthily, this can encourage us to reach goals, get healthier, and earn more money. In an unhealthy way, we obsess, we compare, and we focus on numbers over the big picture.

Artists ideally are coming to you because they like the sound you produce, your artistic flair in your mixes, and the space you create in your masters — not because you’re sitting at number 12 in the mix engineer charts.

I would hope that we can recognise the marketing strategy here. At the end of the day, Muso.Ai is a business that needs to make a profit. The free tier is an excellent crediting platform. The paid tier is buying into our insecurities. If you want to see the analytics of your cumulative work and celebrate the reach, I understand that. Just be mindful when navigating this website that it is not always the best way to grow your career.

I think in an industry where we have some of the worst mental health, we should be careful to be paying to compare ourselves.

The final part is out next Friday.

PS. the whole time I wrote this all I could think of was:

Statistics, statistics, statistics!